On May 7, Trump nominated Casey Means to be the Surgeon General of the United States. A surgeon general is the presidential administration’s voice on health matters. Past surgeons general have used their platform to advise Americans on many life-saving and health-enhancing topics including tobacco use, alcohol abuse, gun violence, breastfeeding, the value of vaccines and vaccine schedules, and pandemic self-protection.

In contrast, Means plans to use her bully pulpit, at least in part, to hawk raw milk, a substance known to be death-dealing. Means has recommended her sister-in-law’s “RAW MILK SMOOTHIE”—Shakeup—on FaceBook, using phrases like “organic ingredients,” “healthy fats,” and “MASSIVE, majorly healthy upgrade.” If her nomination is confirmed, she will undoubtedly be supported in her effort to champion raw milk by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Kennedy claims that’s the only type of milk he will drink.

Yet selling raw milk is illegal in at least 20 states—for good reason. A century ago, tuberculosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever, and infant diarrhea were just four of many diseases spread through raw milk.

What Is Raw Milk?

Raw milk is milk that has not been pasteurized. Pasteurization is short-term heating to a temperature sufficient to kill pathogens, but well short of boiling. The process, which does not involve chemicals, or hormones, or additives, works so well that it’s the reason we no longer worry about milk-borne illnesses. Indeed, pasteurization is a widely recognized and applauded public health triumph.

Advocates of raw milk, on the other hand, argue falsely that pasteurization strips milk of bioactive compounds that prevent cancer and heart disease, and that people who drink raw milk have fewer allergies and are less likely to suffer from asthma than people who drink pasteurized milk. Dieticians and food scientists counter these claims by explaining that any changes to milk caused by pasteurization are negligible.

The current, misguided support for raw milk by MAHA (Make America Healthy Again) influencers makes the historical damage done by unpasteurized milk, especially to small children, worth remembering.

“Slaughter of the Innocents”

In 1900, 13 percent of American infants died before their first birthday; 20 percent of all children died before their fifth birthday. Most died of diarrhea caused by bacteria-laden milk. Diarrhea can be deadly for babies and small children, who have meagre water reserves compared to adults.

The Pure Food and Drug Act passed by the U.S. Congress in 1906 prohibited the sale of adulterated food across state lines, but that left any food manufactured and sold within the same state out of the reach of regulation unless state legislatures and municipalities passed their own pure food laws. And states and cities were slow to do so.

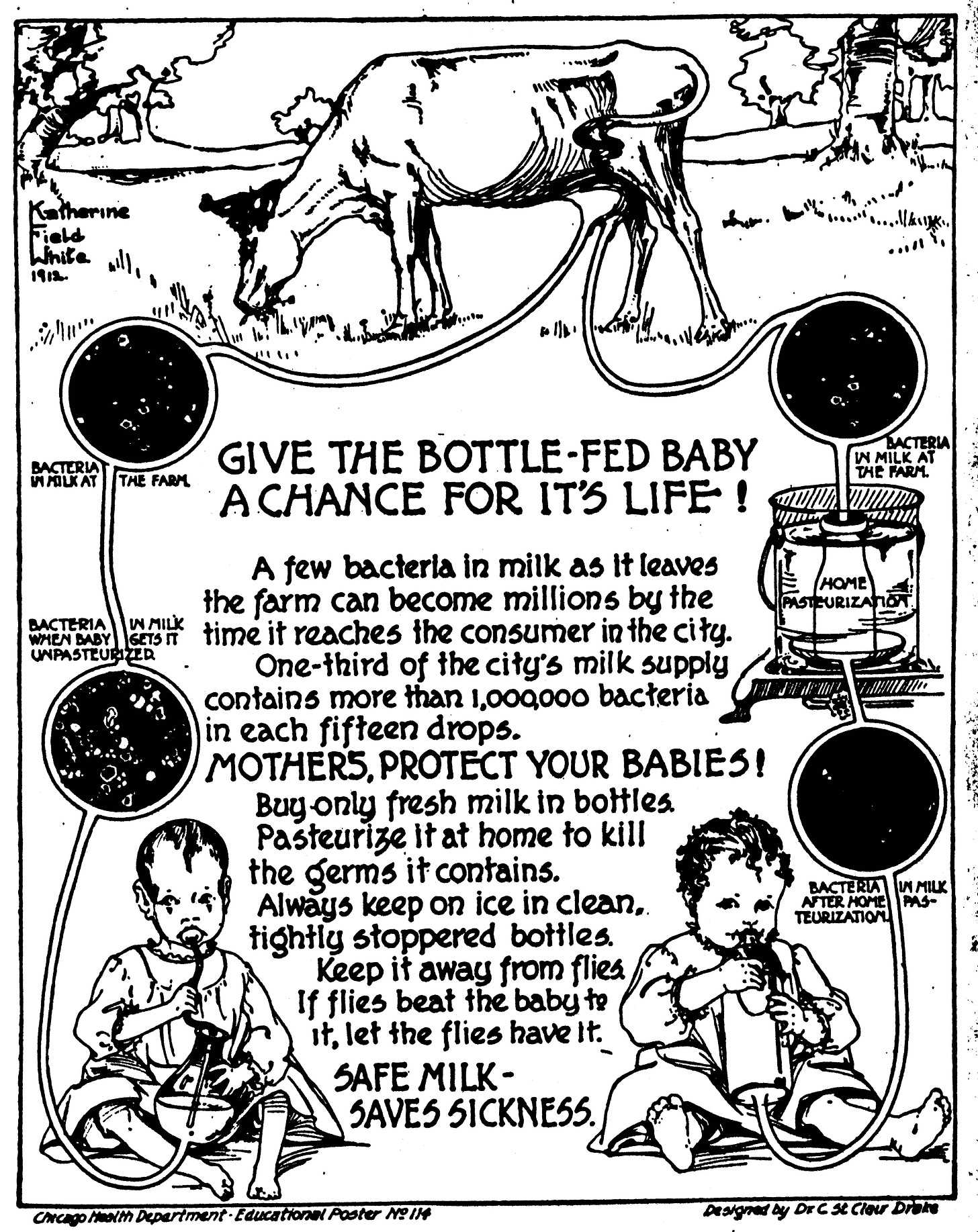

Of all food, milk posed the most serious health threat. As one physician noted angrily in 1910, “It is not a feature of natural selection that babies’ milk should be adulterated or contaminated with germs. Nature gave infants as their birthright their mothers’ milk…without a chance for contamination, without 100 miles intervening for the milk man to bring it.” Public health posters portrayed the problem, illustrating how bacteria multiplies as milk travels from rural farmer to urban consumer, and urging mothers to pasteurize milk themselves at home before giving it to their children.

The decades-long effort to clean up milk in just one city—Chicago—was typical. From 1892 to 1926, to “save the babies,” Chicago’s pediatricians, public health officials, and newspapers crusaded for clean milk. Newspapers dubbed the endeavor “the milk wars,” aimed at ending “slaughter of the innocents.”

When the “wars” began, milk traveled for up to 72 hours from rural dairy farmer to urban consumer. The milk was shipped in 8-gallon vats via unrefrigerated railroad cars, so it spoiled easily, especially during the summer. The vats were uncovered, providing dust, dirt, and flies easy access. The open vats also allowed everyone involved in milk transport and sale—from farmer to shipper to urban merchant to deliveryman—opportunities to increase profits by adding water to the milk, a practice that not only increased the volume of “milk” but also introduced more pathogens from tainted water. Exposure of this practice in 1892 was the first of many milk scandals reported by Chicago newspapers. One article mourned babies “gone to a premature grave” because their “cry for milk was unwittingly answered by a supply of a weak, unnutritious mixture of milk and water.”

Because the milk in uncovered vats took on a grayish cast after days in dusty railroad cars, middlemen and storekeepers also added powdered chalk to the milk to whiten it. Yellow dye was another common additive, used to fool customers into thinking that skimmed milk was rich with cream. Given the number of handlers and lack of safeguards, deliberate adulteration of milk was not the only danger milk posed to the public. Wary customers used a communal dipper (or a finger) to taste-test milk in the open vat before ladling it into their own container, making diphtheria, typhoid, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, polio, and diarrhea—especially infant diarrhea—milk-borne diseases.

Between 1892, when the milk wars began, and 1903, much was written about milk in Chicago—it’s difficult to find a newspaper that didn’t condemn dirty and disease-laden milk near-daily during those years—but nothing concrete was done to fix the situation. Not until 1904 was municipal legislation passed requiring the dairy industry to seal milk vats. In 1912, the vat system was outlawed altogether; henceforth all milk had to shipped and sold in individual, sealed bottles. From 1916 onward all milk had to be pasteurized. Beginning in 1920, milk had to kept cold during shipping. In 1926, the state of Illinois passed legislation requiring that all dairy cattle be tested for bovine tuberculosis and that animals testing positive be killed.

The Fight for Pasteurized Milk

In the decades before the piecemeal passage of laws dictating how milk must be manufactured, shipped, and sold, farmers, dairies, shippers, and merchants fought every legislative effort. The most contentious question was whether to pasteurize milk. Pasteurization was so controversial that the first dairy in the country to pasteurize milk did so secretly. Most dairies argued that the added cost would put them out of business.

But cost wasn’t the only argument against pasteurization. In fact, some of the arguments against pasteurization a century ago are the same arguments used by MAHA influencers today: Pasteurization is unnatural. Pasteurization encourages carelessness because it masks dairies’ worst practices. Pasteurized milk is more difficult to digest than raw milk. Pasteurization destroys milk’s taste. Pasteurization causes malnutrition by destroying milk’s nutritive value. Pasteurization kills some germs, but not all, so pasteurization encourages the creation of super toxic bacteria.

Champions of pasteurization countered that not only were all those claims untrue, but that milk processing and shipping were complex and that, without pasteurization, any misstep could kill a child. If a cow was unhealthy, if a farmer failed to sterilize his hands or the milk pail, if shippers failed to keep milk cold during shipping, if milk was not delivered promptly after arriving in a city, a baby could get sick. Pasteurization was a safe, simple process that guaranteed no misstep would be fatal.

In Chicago, pasteurization never did come to a vote. In 1916, a polio epidemic prompted the Chicago Commissioner of Health to sign an executive order mandating that all milk sold in the city be pasteurized. He feared that polio might become a milk-borne disease, as it had in a few other cities.

With each mandate—from covering vats to bottling to pasteurizing to keeping milk cold—infant deaths from diarrhea decreased a bit more until the scourge was virtually eradicated. In 1897, when Chicago had a population of only 430,000, diarrhea caused 53.7% of the 5,735 deaths of children under the age of two that year. In 1924, when the city had ballooned to a population of almost three million, diarrhea caused 16.9% of the 4,528 infant deaths that year. And by 1939, with the milk supply cleaned up and long before medicine had any adequate treatment for infant diarrhea, only 1.4% of 1,533 infant deaths in Chicago was from diarrhea. Other municipalities saw similar reductions in diarrheal deaths with the passage of their own laws governing the manufacture and sale—but especially the pasteurization—of milk.

Raw milk has a long, deadly history that should have ended with pasteurization. But as long as raw milk has adherents, it will continue to sicken and kill. Between 1998 and 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration traced more than 200 disease outbreaks to raw milk. Kennedy’s and Means’s rejection of history and established knowledge promise to link disease once again to milk. It’s time to remind yourself, your family members, your friends, your neighbors, and your political representatives that laws regulating milk are life-savers, not industry or job or product killers.

Jacqueline H. Wolf is professor emeritus of social medicine, Ohio University, and the author of Don’t Kill Your Baby: Public Health and the Decline of Breastfeeding in the 19th and 20th Centuries (Ohio State University Press, 2001).

Sources

Fenit Nirappil, “Uproar over surgeon general pick exposes MAHA factions among RFK Jr. allies,” Washington Post, May 9, 2025, available HERE.

Meredith Evans, “Gwyneth Paltrow Talks Motherhood, MAHA, and the Raw Milk Revolution,” Evie March 18th, 2025, available HERE.

Alyssa Goldberg, “These influencers, RFK Jr. can’t get enough raw milk. But what about bird flu?” USA Today, February 4, 2025, online HERE.

Jacqueline H. Wolf, Don’t Kill Your Baby: Public Health and the Decline of Breastfeeding in the 19th and 20th Centuries (Ohio State University Press, 2001), Chapter 3, “Slaughter of the Innocents: Infant Mortality and the Urban Milk Supply,” 42-73.

Richard A. Meckel, Save the Babies: American Public Health Reform and the Prevention of Infant Mortality, 1850-1929 (Johns Hopkins University Press), 1990.

Samuel H. Preston and Michael R. Haines, Fatal Years: Child Mortality in Late Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton University Press), 1991.

“The Dangers of Raw Milk: Unpasteurized Milk Can Pose a Serious Health Risk,” FDA: An official website of the United States government, online HERE.