The Suspension of PRAMS Ignores 100+ Years of Public Health Practice

Janet Golden and Jacqueline H. Wolf

For well over a century, the U.S. government has supported efforts to collect data on maternal and infant health so that government could educate families about health risks, and fund state and local services that support at-risk families. One payoff of these initiatives has been a greatly lowered infant mortality rate, from 13 deaths per 100 live births in 1900 to 0.56 deaths per 100 live births today.

Since 1987, the main driver of lowering infant mortality in the United States has been the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), a division of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). For almost 40 years, PRAMS has amassed data to identify at-risk mothers and babies, and disseminate pertinent information to influence maternal behaviors before, during, and after pregnancy. State governments, in turn, have used PRAMS data to develop their own maternal and infant health programs. Data gathering is a vital function of government, and for decades the CDC website has documented the link between PRAMS data and improved maternal and infant health.

Yet despite PRAMS success, in late February news outlets reported the suspension (allegedly temporary) of PRAMS activities along with the disappearance of its website displaying current data. Then, on April 1, as part of the layoffs decimating the Department of Health and Human Services, the entire PRAMS staff was placed on “administrative leave.”

Because PRAMS identifies populations according to race, sexual orientation, sexual identity, and socioeconomic status—all categories used historically by public health workers to identify at-risk groups—the monitoring system ran afoul of the Trump administration. According to Trump, classifying people by race and sex constitutes “illegal and immoral discrimination.” Yet investigating the factors that determine who is at-risk for preventable illnesses and deaths has never been a “woke” DEI project. It is a core requirement of public health work and thus a government responsibility.

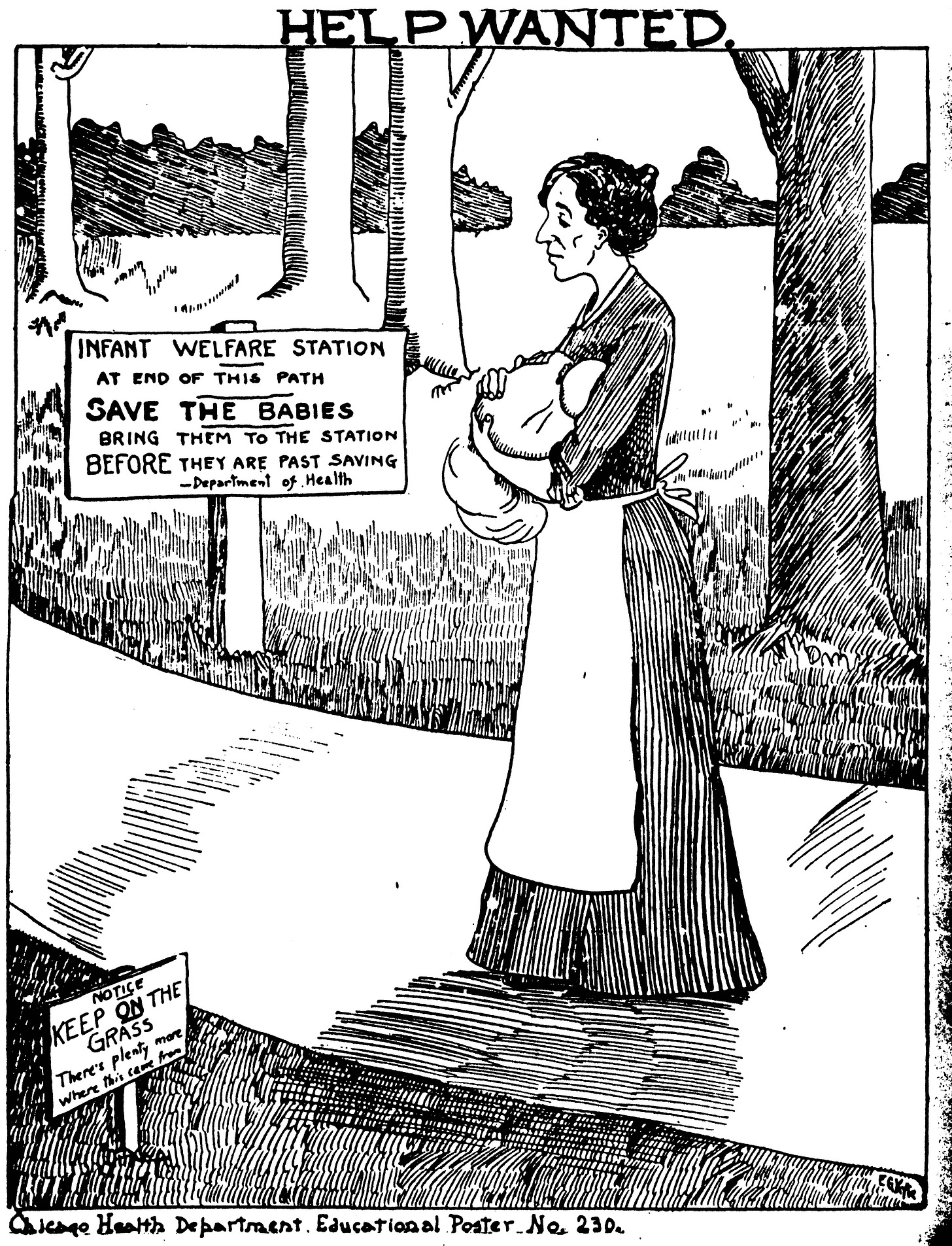

U.S. government efforts to lower maternal and infant mortality can be traced back to programs initiated in the early 20th century by the U.S. Public Health Service, although the full flowering of programs did not occur until the U.S. Congress and President William Howard Taft created the United States Children’s Bureau in 1912 to investigate the causes of infant and child mortality. The Bureau looked at variables that included income and race, and distributed pamphlets on prenatal and infant care to educate pregnant women and new mothers. Local and state governments then used the findings of the Children’s Bureau to design their own public health measures. When the data indicated, for example, that the primary cause of infant death was dehydration from diarrhea, local governments and state legislatures passed laws requiring that cows’ milk be pasteurized, sold in individual sterile bottles, and kept cold during shipping. In 1921, Congress continued its efforts to save the lives of mothers and children by passing the Maternity and Infant Protection Act, also called the Sheppard-Towner Act, to provide funds to the states for public health education, pre- and postnatal home visits from nurses, and maternity and child healthcare centers. During World War II, Congress’s Emergency Maternity and Infant Care Act dispensed federal dollars to cover the prenatal, delivery, and postnatal care of the wives of servicemen in the lowest four pay grades, ultimately paying for more than 1.2 million—that is, one in seven—births between 1943 and 1949 during an era when private health insurance did not cover childbirth.

These programs saved lives, just as the work of PRAMS has since 1987. But the work is far from finished and indeed must remain ongoing.

Maternal and infant mortality rates in the United States are higher than in other developed countries. While our current 0.56% infant mortality rate is a vast improvement over 120 years ago, the infant mortality rate in Japan is only 0.16%, in Norway 0.18%, and in Australia 0.2%. Maternal mortality in the U.S. is also high compared to other wealthy countries. In 2020, for every 100,000 births in Norway, 1.66 mothers died, in Australia 2.94, and in Japan 4.31. In contrast, in the United States in 2020, 21.1 mothers died for every 100,000 births. Racial disparities account for much of the gap. At 69.9 deaths per 100,000 births, maternal mortality among African Americans is more than three times higher than the overall maternal death rate.

That is why ceasing to gather data according to traditional categories, and ceasing to make the data available to states and cities, is literally life-threatening. The CDC devised PRAMS, in part, to better understand why Black mothers have had significantly worse birth outcomes than white mothers. That initial investigation required that PRAMS data be organized in several different ways, including according to the race of the mother. And that is also why the Trump administration suspended the program and why—if or when the program is revived—CDC employees have been forbidden to note race when collecting future data. But if you don’t ask the right questions, you won’t get the answers you seek, and you can’t develop the policies that will help the federal government and state governments fix identifiable problems. That is Public Health 101.

At the turn of the twentieth century, public health officials understood that focused inquiries and careful data collection would lead to effective interventions in support of safe births and healthy mothers and infants. Reshaping PRAMS to fit a political agenda is a repudiation of more than a century of accumulated knowledge and effective public health work. Saving lives is not a DEI project. It is a public health project.

Janet Golden is Professor Emeritus of History, Rutgers University. Jacqueline H. Wolf is Professor Emeritus of Social Medicine, Ohio University.

Sources

Josh Marshall, “CDC Shutters PRAMS Program on Maternal and Infant Health,” TPM, February 22, 2025, Marshall, CDC Shutters PRAMS.

Sarah D. Wire, Josh Meyer, et al, “Mass layoffs hit workers at HHS; sweeping cuts extend to CDC, NIH, FDA: Recap,” USA Today, April 1, 2025, Mass Layoffs Hit HHS, accessed April 4, 2025.

President Donald J. Trump, “Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing, January 20, 2025, Trump Executive Order Ending DEI, accessed April 1, 2025.

Josh Marshall, Marshall J. “Why PRAMS Got Shuttered,” TPM, February 23, 2025. Marshall, Why PRAMS Got Shuttered, accessed April 1, 2025.

World Health Organization. Maternal, Newborn, Child, Adolescent Aging, WHO Data, accessed April 1, 2025.

Richard A. Meckel, Save the Babies: American Public Health Reform and the Prevention of Infant Mortality, 1850-1929 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990).

Kriste Lindenmeyer, “A Right to Childhood” The U.S. Children’s Bureau and Child Welfare, 1912-1946 (University of Illinois Press, 1997).

Jacqueline H. Wolf, Don’t Kill Your Baby: Public Health and the Decline of Breastfeeding in the 19th and 20th Centuries (Ohio State University Press, 2001).

Janet Golden, Babies Made Us Modern: How Infants Brought Americans into the Twentieth Century (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Thank you for shedding light on such a timely and urgent topic.

Great illustration! “Keep on the grass!”