As the corruption in the Trump administration becomes ever more brazen, it is increasingly stunning to hear members of the administration rail against the financial entanglements of physicians, federal agencies, and government scientists with the food and pharmaceutical industries. It is especially stunning when the criticisms come from officials who conceal the profits they derive from the wellness industry. Here we focus on those who promote dietary supplements.

Between 1994 and 2022, the market for dietary supplements grew from a 4 billion dollar industry with 4,000 products to a 40 billion industry with 80,000 products. Although supplements are not regulated for safety and efficacy, they are widely advertised so it’s no surprise that approximately 80 percent of Americans report that they have taken at least one.

This is not the first time that Americans have ingested drugs from manufacturers who operate with little regulation. In the nineteenth century, the drugs most widely consumed were known as patent medicines. The label was a misnomer. Loath to disclose the contents of their products, most proprietors did not even try to obtain patents.

Most 19th-century nostrums were more likely to harm than to help. Their ingredients included alcohol, opium, cocaine, and even radium. After the announcement of the Curies’ sensational discovery, “Dr.” William J. A. Bailey’s Radithor, a liquid radium solution, became extremely popular. One delighted physician wrote to his colleagues: “There are always times in our busy life when the work comes so fast that we are tired out.” The effect of Radithor on fatigue “is simply magical, as I can testify. In my own case I pass, in about twelve hours, from exhaustion to one of perfect well-being, and this condition persists.” But not all customers were so fortunate. After the slow and painful death in 1932 of Eben M. Byers, a socialite and industrialist, a front-page article in the New York Times announced that he had died of radium poisoning.

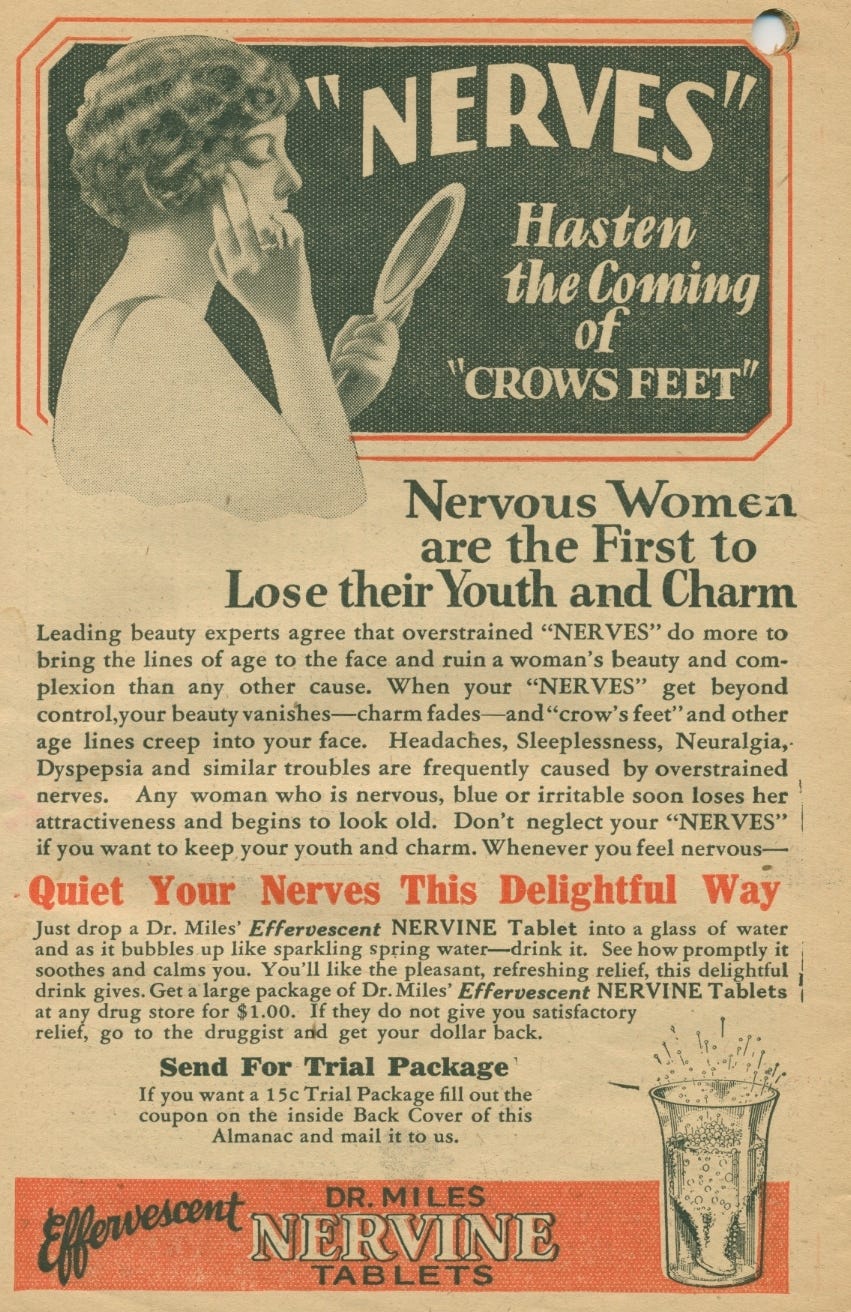

Patent medicine manufacturers (labeled “toadstool millionaires” by Oliver Wendell Holmes) placed advertisements in both medical journals and mass-market magazines, invoked expert testimony, and like Bailey, employed hyperbolic language. The Doctor Miles Medical Company in Elkhart, Indiana, which sold various “restorative” medicines, touted its best seller, “Restorative Nervine,” as “a brain and nerve food and medicine, which soothes and quiets the brain and nervous system while it furnishes nourishment and strength.”

Ludicrous as such assertions appear today, they must have been convincing. In 1859 proprietors earned $3,500,000. By 1904, the sum had grown to $74,500,000 (nearly $4 billion in 2025 dollars), a more than twenty-fold increase. But as profits rose, wellness medicines encountered increasing hostility. The influential Women’s Christian Temperance Union condemned the large amount of alcohol in many nostrums. Physicians denounced the manufacturers as quacks and their products as either useless or dangerous.

In 1905, the critics received support from the muckraking journalist Samuel Hopkins Adams, who published a series of devastating articles in Collier’s Weekly on the “The Great American Fraud.” The first article in the series began: “Gullible America will spend this year some seventy-five millions of dollars in the purchase of patent medicines. In consideration of this sum it will swallow huge quantities of alcohol, an appalling amount of opiates and narcotics, a wide assortment of various drugs ranging from powerful and dangerous heart depressants to insidious liver stimulants, and, in excess of all other ingredients, undiluted fraud.” Adams’s diatribe helped pave the way for the passage of the 1906 Food and Drug Act requiring manufacturers to list the ingredients in their products. The Act was one of the first major pieces of consumer legislation. Subsequent laws further restricted the patent medicine industry and led to its decline.

We tend to view 19th-century patent medicines as evidence of the mistaken beliefs of a by-gone era, but the dietary supplements many Americans buy today have certain similarities. Supplement manufacturers engage in aggressive marketing and make exaggerated claims that cannot pass scientific muster. Some supplements contain harmful ingredients and interact with other medications. A 2015 article in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that “adverse events” from supplements send 23,000 people to the emergency room each year.

Unlike companies that make prescription and over-the-counter medications, supplement manufacturers are not permitted to assert that their products can prevent or cure particular diseases. The Food and Drug Administration allows them only to state that they can improve overall health. Today’s manufacturers thus make nebulous claims about “boosting energy” or “fighting fatigue,” confident that those assertions cannot easily be challenged.

Many people currently in Trump’s administration, or nominated for a top post in Robert F. Kennedy’s Department of Health and Human Services, embrace dietary supplements and benefit financially from promoting them. Calley Means, a White House adviser who has no medical background and who previously ran a company selling bridal dresses, has called the American Medical Association “a pharma lobbying group” and the Food and Drug Administration “a sick puppet of industry.” Means is also the co-founder of TrueMed, an online platform that sells dietary supplements and other wellness products.

Calley Means’ sister is Casey Means, the nominee for U.S. Surgeon General despite her lack of a current medical license. The two siblings are both online “wellness influencers” and authors of the New York Times bestseller Good Energy, which contends that metabolic dysfunction is responsible for 80 percent of all illnesses, an argument that many scientists dispute and some dismiss as a fad.

“Why do I stick with a fairly intensive supplement strategy?” Casey Means asked in a recent newsletter. “Because I find that it works for me: I feel incredibly energetic, have no chronic symptoms, my overall health biomarkers are very good, and my biological age is 19.7, and has been declining!” (Her chronological age is 36; she does not indicate how she calculates her biological age.) Like her brother, she decries the close connection between scientists and food and pharmaceutical companies. “There’s huge money, huge money going to fund scientists from industry,” she has said. “We know that when industry funds papers, it does skew outcomes.” Excoriating the involvement of food companies in constructing the Food and Drug Administration Dietary Guidelines, she scolded, “We need unbiased people writing our guidelines that aren’t getting their mortgage paid by a food company.”

But Casey Means has her own conflicts of interest. She does not consistently disclose her financial relationships with wellness companies. She does acknowledge that supplement companies sponsor her newsletter and even admits that their relationship is a “little messy.” However, although she lists herself as an “Investor and/or Advisor” of Zen Basil, a supplements company, she does not always disclose that information when she tells her many followers on Instagram, X, and Facebook to buy the company’s products.

Mehmet Oz, who calls himself “America’s Doctor,” is the Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services although experts estimate that only half of the claims he made on his popular talk show were true. His current Trump administration appointment probably owes much to his promotion of hydroxychloroquine, the dangerous medication Trump recommended during the Covid pandemic. In 2014, Oz agreed to a $5.25 million settlement in a class action lawsuit that accused him of exaggerating the benefits of weight-loss supplements. In a Senate subcommittee on consumer protection that year, Claire McCaskill, then a Democratic senator from Missouri, quoted his words, which are eerily reminiscent of the rhetoric of patent medicine hawkers: “You may think magic is make-believe, but this little bean has scientists saying they’ve found the magic weight-loss cure for every body type—it’s green coffee extract.”

In addition to weigh-loss supplements, Oz has promoted fish oil pills to prevent heart disease, despite studies reporting that they may increase the chance of developing irregular heartbeats. In December 2024 Robert Weissman, co-president of Public Citizen, a watchdog group, sent a letter to the Federal Trade Commission complaining that Oz “posts regularly with appeals to consumers to consider buying products from iHerb. Video posts do not disclose his financial connections, nor does the accompanying text.”

The conflicts of interest of Calley Means, Casey Means, and Mehmet Oz may pale when compared to the other corruption that is rife in the Trump administration. But Casey Means and Oz are charged with protecting the nation’s health. They cannot Make America Healthy Again by hawking products that earn them money but have little, if any, real value and may instead harm anyone who consumes them.

Sources

Casey Means, “Newsletter #29: Supplements 101: Choosing and Dosing Vitamins + Minerals,” September 24, 2024, www.caseymeans.com.

Casey Means with Calley Means, Good Energy: The Surprising Connection between Metabolism and Limitless Health (Avery, 2024).

Sophia V. Hua, “A Content Analysis of Marketing on the Packages of Dietary Supplements for Weight Loss and Muscle Building,” Preventive Medicine Reports, July 2023.

Dani Blun, Nina Agarwal and Saurabh Datar, “Dr. Oz Became Famous Giving Health Advice: Was It Any Good?,” New York Times, March 14, 2025.

Elizabeth Richardson, Farzana Akkas, and Amy B. Cadwallader, “What Should Dietary Supplement Oversight Look Like in the US?,” AMA Journal of Ethics, May 2022.

“Trump’s Surgeon General Pick Criticizes Others’ Conflicts but Profits from Wellness Product Sales,” Associated Press, June 6, 2025.

National Institutes of Health, “Dietary Supplements for Weight Loss: A Fact Sheet for Health Professionals,” May 2022, https://ods.od.nih.gov.

Federal Trade Commission, “Marketer Who Promoted a Green Coffee Bean Weight-Loss Supplement Agrees to Settle FTC Charges,” January 26, 2015, https://www.ftc.gov.

Andrew I Geller, et al., “Emergency Department Visits for Adverse Events Related to Dietary Supplements,” New England Journal of Medicine, October 15, 2015.

Emily K. Abel is professor emerita at the UCLA-Fielding School of Public Health. She is the author of many books. The most recent is Gluten Free for Life: Celiac Disease, Medical Recognition, and the Food Industry (NYU Press, 2025).